We support people’s mental health at work by creating an environment for thriving, eliminating harmful parts of work or providing tools to manage parts of the job we know can create harm, and supporting people who are experiencing problems. This article focuses on preventing mental health problems due to work and preventing work from making latent mental health problems worse. Another article focuses on workplace activities to support people with mental health problems.

Scientific studies encompassing large populations viewed over time show that workplaces with high resources have healthier people and higher productivity1 . Healthy workplaces are part of the United Nations’ social development goal #8 because healthy workplaces creates healthy work and maximizes everyone’s ability to participate in the workforce. Good help is hard to find – so we need everyone working.

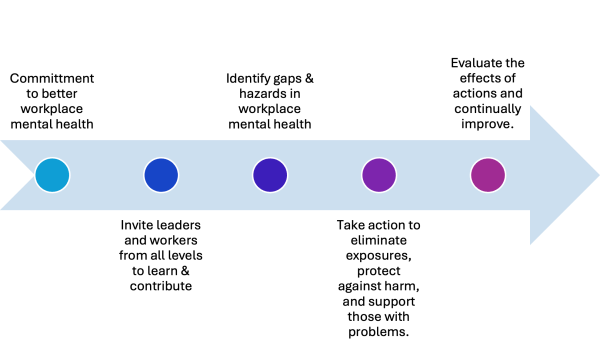

Psychologically healthy workplaces are formed, in part, by commitment of the owners or top management to:

- Involve workers in designing work processes and seeking consultation on work that may cause strain or additional stress.

- Demonstrating commitment for employee health and business outcomes.

- Following through by monitoring and communicating the effect of changes in continuous quality improvement.

This positive Psychosocial Safety Climate enables other great workplace factors2.

There are many activities, demonstrated by research, that positively impact employee health. The key is that these activities must fit the organizations’ situation. For example, a 4-day workweek may be shown to be helpful in a tech company but could actually be harmful to a refinery where the “office” works four ten-hour shifts/week but that impacts production because key decision makers are absent when needed and supervisors on shift cannot make decisions. Or, a mindfulness program may have shown promise in workplace X but workplace Y tried that same program and it did not work. The key is workplace X had high trust and ways of managing peak workloads as a team but workplace Y lacked that finesse so the program was seen as a disingenuous band aid while management ignored the lack of teamwork and efficiency during peak workloads.

Deciding what you will do will depends on what you find when you involve employees in your mental health strategy. Are you concerned about inviting employee participation? If so, please ask yourself:

- What do I fear if I invite employee participation?

- Do I worry I cannot deliver on their wishes? Do I need to grant wishes? Isn’t it management’s job to run the organization?

- What am I missing by not getting feedback from employees?

- What if employees do have valuable input on how to smooth out rough spots and improve employee experience and productivity?

- What if employees are experiencing bullying, harassment, frustration, and stress and not telling us – what are they doing then?

In Canada, most workplaces have a joint health and safety committee and this is the most logical place to start and begin the trust-building process of employee collabouration. Please contact me to learn more about education and consultation that aligns with your business.

Eliminating/limiting exposure to harmful work factors

Scientific research shows work can be harmful. We are all aware that asbestos exposure causes death much, much later. But what about the effect of job strain and long working hours? What about being exposed to bullying at work? Would people come to work for you if they knew job strain, long hours, or bullying could be expected? The pooled results of numerous scientific studies indicates being exposed to the following creates risk. Some of these include:

Job strain (high job demands, low control over how is done) or effort-reward imbalance:

- 48% increase of coronary heart disease if 1 factor present or 103% increase in risk of a cardiac event if 2 present3

- 17 – 45% increased risk of coronary heart disease, 9 – 22% increased risk of stroke, 8 – 29% increased risk of diabetes, 35 – 62% risk of MSD4.

- 14 – 77% increased risk of depression5 and 15 – 35% of depression in working people may be attributed to job strain6

Long working hours, often defined as working more than 50 hours per week has risk of4:

- 21 – 38% risk of pre-term delivery or miscarriage.

- 54% increased risk of breast cancer

- 8 – 48% increased risk of depression

- 21 – 35% increased risk of stroke

People exposed to bullying are at 2.58x increased risk for depression5.

This and similar evidence has led the WHO and many national governments to take action on preventing exposure to workplace factors which can cause psychological harm. In Canada the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health & Safety in the Workplace breaks down these workplace factors into 13 groups. These factors can be helpful or harmful, depending on what they are. For example challenging job demands, when supported by adequate resources, build health and motivation whereas boredom and under-employment is a health hazard. Transformative leadership is a job resource whereas negative, abusive supervision is a health hazard. Learning about workplace factors and how they show up in your workplace is a good starting point to improving workplace mental health. A structured risk assessment, just like for physical hazards, applies to these psychosocial job factors. The detail and complexity of your risk assessment depends on your organizations’ size, complexity, workforce, and many other factors.

Once job hazards are identified, just like in traditional occupational health and safety, can be treated with the hierarchy of controls: eliminate hazards and then mitigate the risk of hazard by job re-design, teaching protective strategies, and personal protective equipment. New Zealand has a great worked example of this here.

After controls are devised and implemented continuous quality improvement processes apply: evaluate if/how the controls were enacted, effects of controls, and revise the controls as needed.

Please contact me to learn more about education and consultation that aligns with your business.

Where does equity, diversity, inclusion, and accessibility fit?

Research is clear that equity-deserving groups experience workplace factors differently. Intersectionality, how various factors impinge in one place, can amplify workplace factors to a harmful threshold. When looking at workplace mental health, under-represented groups’ experience won’t necessarily be seen in surveys or focus groups and organizations must go out of their way to solicit input and ensure those groups are not being harmed. Input from employee resource groups, EDI (equity, diversity, inclusion) committees, and outside stakeholders can help uncover how these groups may experience workplace factors. Groups to consider seeking input from include:

- LGTBQ2S+

- Newcomers to Canada

- Visible minorities

- Employees with disabilities

Please contact me to learn more about education and consultation that aligns with your business.

- Nielsen, K., Nielsen, M. B., Ogbonnaya, C., Känsälä, M., Saari, E., & Isaksson, K. (2017). Workplace resources to improve both employee well-being and performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 31(2), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1304463 ↩︎

- Dollard, M. F., Dormann, C., & Idris, M. A. (2019). Psychosocial Safety Climate: A New Work Stress Theory and Implications for Method. In M. F. Dollard, C. Dormann, & M. Awang Idris (Eds.), Psychosocial Safety Climate (pp. 3–30). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20319-1_1 ↩︎

- Lavigne-Robichaud, M., Trudel, X., Talbot, D., Milot, A., Gilbert-Ouimet, M., Vézina, M., Laurin, D., Dionne, C. E., Pearce, N., Dagenais, G. R., & Brisson, C. (2023). Psychosocial Stressors at Work and Coronary Heart Disease Risk in Men and Women: 18-Year Prospective Cohort Study of Combined Exposures. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 16(10). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.122.009700 ↩︎

- Niedhammer, I., Bertrais, S., & Witt, K. (2021). Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: A meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 47(7), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3968 ↩︎

- Rugulies, R., Aust, B., Greiner, B. A., Arensman, E., Kawakami, N., LaMontagne, A. D., & Madsen, I. E. H. (2023). Work-related causes of mental health conditions and interventions for their improvement in workplaces. The Lancet, 402(10410), 1368–1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00869-3 ↩︎

- Niedhammer, I., Sultan-Taïeb, H., Parent-Thirion, A., & Chastang, J.-F. (2022). Update of the fractions of cardiovascular diseases and mental disorders attributable to psychosocial work factors in Europe. International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health, 95(1), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-021-01737-4 ↩︎

- Niedhammer, I., Bertrais, S., & Witt, K. (2021). Psychosocial work exposures and health outcomes: A meta-review of 72 literature reviews with meta-analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health, 47(7), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3968 ↩︎

- Rugulies, R., Aust, B., Greiner, B. A., Arensman, E., Kawakami, N., LaMontagne, A. D., & Madsen, I. E. H. (2023). Work-related causes of mental health conditions and interventions for their improvement in workplaces. The Lancet, 402(10410), 1368–1381. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00869-3 ↩︎