Healthy work nurtures healthy people who power organizations and society. Work is an important component of life: a source of accomplishment, purpose, social connection, and a means to an income. Work has many positives. Overall, working is associated with better health and wellbeing[i] but poor working conditions are associated with poor health. Situations of high job demands, low control and low input into how work is done as well as unclear expectations and breach of psychological contract are shown to influence development of mental health problems[ii]. Further, unhealthy or even worse, “toxic” workplaces are plagued by high turnover and absenteeism and those trapped in those workplaces stay because they must and at the cost of their health and organizational effectiveness.

Psychological Health and Safety is systematically addressing risk

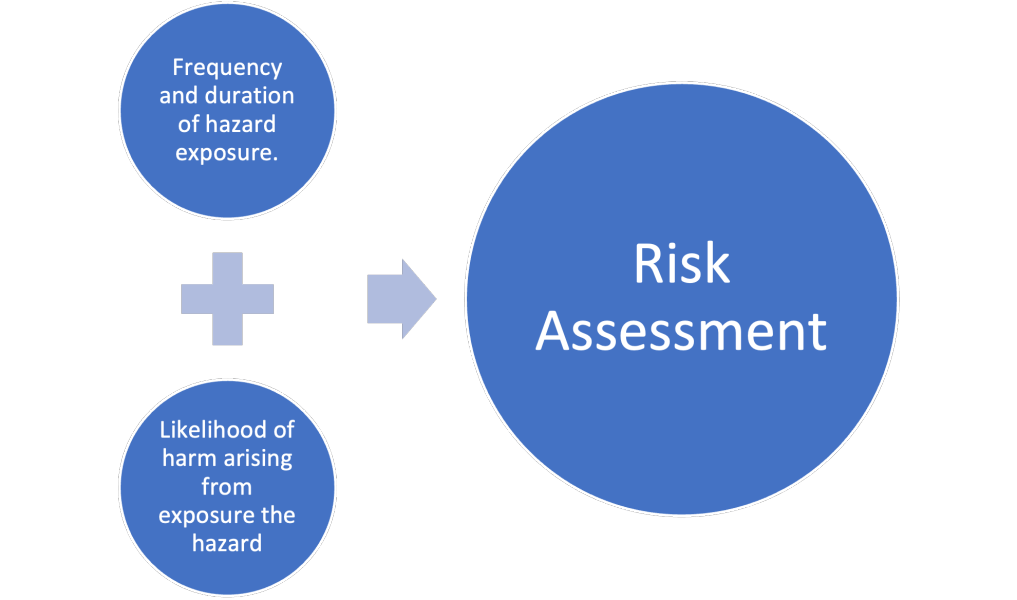

Psychosocial hazards, that is the things we encounter at work which cause an undesirable emotional or cognitive response, carry a risk of harm with exposure. Risk assessment processes determines the potential and severity of harm that can come from exposure. For example, working on a roof carries risk of falling and causing severe injury. The frequency of falling is relatively low but the potential for harm is high, and therefore a prudent risk assessment indicates the activity should be eliminated or if performed, done only by trained personnel in a falls arrest harness under supervision. Similarly, many customer-facing businesses in their risk assessment recognize that verbal abuse occurs commonly and that chronic or episodic exposure carries high risk of harm, and take steps to limit harm. They limit exposure by training employees to de-escalate situations, create quick pathways to transfer abusive customers to managers with decision authority, and may even terminate relationships with abusive clients. Those same organizations may also provide follow up debriefing and/or counselling to assist with stress response of their employees.

Psychosocial hazards are not always as obvious as witnessing trauma or being berated by an angry customer. There is strong evidence across many research studies that job strain and other adverse work conditions are high risks for physical[iii] and mental health[iv] problems. A recent large study found 11% of Canadians sampled had working conditions that put them at 7.5 times the risk of burnout[v]. Burnout is associated with poor health[vi] in ways such as heart disease, pain, insomnia, and mental health problems[vii]. Under law, employers have a duty of care to provide a safe workplace by assessing and acting on the risks to health but legislation on what hazards to address varies from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. For example, most Canadian provinces require employers to protect against bullying and harassment and the Canadian Labour Code goes further and requires employers to investigate psychosocial hazards which may contribute to harassment and violence. However, other known hazards such as unclear or unrealistic job output expectations are not hazards required to be addressed.

How to get started

Best practice in workplace psychological health and safety is involving all levels of an organization in a wholistic manner to identify risks to wellbeing and plan for action. For most organizations, large or small, this can seem daunting. But many organizations already have job resources that are protective and nurturing and starting an inventory of these and a work plan can create some forward momentum. Starting to work on compliance to a gold standard such as the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace or ISO 45003 can come down the road but to get started, the Centre of Addictions and Mental Health (CAMH) recommends the following[viii]:

- Start where you are and create a strategy you can revisit, expand, and revise: determine what good mental health means for your organization and what outcomes you want to achieve by what means. Starting small is better than not starting. Revisit the strategy often, as you measure the impact and monitor the means. Strategy can be informed by selecting and evaluating current key performance indicators (KPIs) as well as formal or informal psychosocial risk hazard assessment.

- Train leaders to be mental health aware and what it means to be a psychologically healthy leader: healthy themselves but also ones who respond and lead in ways that foster their followers’ wellbeing.

- Have supports that work for your people where they are at – this could be a combination of a mentorship program, peer support program, employee-family assistance program (EAP), enhanced access to medication in the extended health plan, or flexible leave policies – supports that make sense for your workforce.

- Support employees with illness and those who are on leave or at risk of work absence with job accommodations and additional supports.

- Track progress and learn and adjust process.

Getting started can be the hardest part. Many people just want to “get something done” and may rush to ineffective services such as employee lunch and learns on resilience or buying a peer support training program without an implementation and maintenance plan. Then, when outcomes are not achieved, they move on to the next thing. How can you and your organization get started?

Find a high-quality consultant who understands the larger picture of workplace mental health and won’t sell quick fixes or motivational speeches but will partner with you to create actual change. These consultants often have advanced training in the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace or a wealth of experience in similar methods. Ask for references and choose consultants with sustained and successful engagements.

Or

Take time to learn about the National Standard and the landscape of workplace mental health by reading some elements of this reading list and then when ready, self-serve with tools from the Workplace Strategies for Mental Health website.

The journey is worth it. My perspective is working with clients who have had poor work environments or at very least, encountered difficult periods in life with an indifferent or uncaring employer. If the suffering they endured can be eliminated or reduced for someone else, all this effort is worth it. We can make work great for everyone.

[i] Maaike van der Noordt et al., “Health Effects of Employment: A Systematic Review of Prospective Studies,” Occupational and Environmental Medicine 71, no. 10 (October 2014): 730–36, https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2013-101891.

[ii] Henk F van der Molen et al., “Work-Related Psychosocial Risk Factors for Stress-Related Mental Disorders: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” BMJ Open 10, no. 7 (July 2020): e034849, https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034849.

[iii] Yacine Taibi et al., “A Systematic Overview on the Risk Effects of Psychosocial Work Characteristics on Musculoskeletal Disorders, Absenteeism, and Workplace Accidents,” Applied Ergonomics 95 (September 2021): Article 103434, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apergo.2021.103434.

[iv] van der Molen et al., “Work-Related Psychosocial Risk Factors for Stress-Related Mental Disorders.”

[v] Faraz V Shahidi et al., “Assessing the Psychosocial Work Environment in Relation to Mental Health: A Comprehensive Approach,” Annals of Work Exposures and Health 65, no. 4 (May 1, 2021): 418–31, https://doi.org/10.1093/annweh/wxaa130.

[vi] Christina Maslach and Michael P. Leiter, “Understanding the Burnout Experience: Recent Research and Its Implications for Psychiatry,” World Psychiatry 15, no. 2 (June 2016): 103–11, https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20311.

[vii] Salvagioni et al., “Physical, Psychological and Occupational Consequences of Job Burnout.”

[viii] Centre for Addictions and Mental Health, “CAMH Mental Health Playbook for Business Leaders” (CAMH), accessed March 24, 2020, https://www.camh.ca/en/health-info/workplace-mental-health-playbook-for-business-leaders.