The world of work can be really turbulent. Some are surfing the crests of those waves and others feel like they are being pulled under. I would be really interested to see an evidence-informed human capital strategy that fits employee engagement, workforce sustainability, and occupational health all on one page – if you’ve seen it please message me and I’d love to view it. However, from a workplace mental wellbeing perspective, the integrated approach proposed by Tony Lamontagne and colleagues in 2014[i] really resonates for me:

- Promote the positives of work because good work is motivating and working supports wellbeing. Let’s make work even better by optimizing jobs for the human beings that do them.

- Prevent harm because humans are more important than business output. We know there are hazards at work – things that can harm. For example, the power saw which speeds up construction astronomically has the risk to cut off your hand. And being exposed to a workplace with bullying or pressure to perform work on off hours due to “always on technology” are both risks for mental health problems.

- Support those affected by ill-health so they can recover and flourish again whether the origin was work-related or not in order to sustain human capital.

Some people think a workplace mental health program is only supporting those with mental health problems. But that is really a mental ill-health program. The Mental Health Continuum and some psychological theory can help create a comprehensive explanation of where different workplace mental health activities fall.

The Mental Health Continuum[ii] was created to help people evaluate their mental health, acknowledging that a mental health diagnosis does not mean you are living well or are ill and those without a diagnosis are also on the same continuum. The original continuum features only the heading but I have added the captions as I think it describes in more detail what we experience.

Using Statistics Canada data[iii], we can assume that about two-thirds of Canadians mental health is “very good” or “excellent” and would likely be in the green category. About 27% feel work is often stressful and 12% would have psychological distress[iv] and likely be in the orange and red category with a diagnosed mental health disorder[v]. Both the previous studies note rates of distress and mental health diagnoses almost double in lower income and unemployed situations and improve with high income.

The well-accepted Conservation of Resources (COR) Theory[vi] states that when we are healthy and resources are plentiful we thrive and can take on new learning but when we are threatened and feel like our resources are not enough, we often turn inward and don’t access new resources. Research into the Job-Demands Resources (JD-R)[vii] model has shown when job resources (e.g. challenge, training, supervisor support, autonomy) are high and employees are well, employees are engaged and there is an upward spiral of performance. Conversely when job demands like cognitive complexity, poor system alignment, or poor manager support are present common mental health problems, burnout, and low job performance are more prevalent.[viii] Even worse, those feeling “under the gun” or likely in the yellow, orange, or red on the continuum, are more likely to engage in unintentional self-undermining behaviours like pulling away from others, substance use, or unhelpful workplace communication.[ix] Those who are not well are often present but not productive, have increased errors, and production losses are significant[x]. So what’s the take away?

- Healthy people are more able to use job resources.

- People feeling strain need support & resources brought to where they are.

So how does this inform workplace mental health activities?

The overall workplace environment matters.

The reference standards for workplace mental health across the globe, ISO 45003[xi], the HSE Management Standards[xii], and the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace[xiii], all point to four imperatives:

- Management commitment to employee wellbeing.

- Joint involvement of employees in creating good work.

- Identification of risk factors for poor mental health and acting on those risks.

- Continual process improvement.

Research indicates positive Psychosocial Safety Climate[xiv] (PSC), a workplace where team members feel the organization values their health over production and there is input and dialogue as to how work is done, creates an environment that allows other positive workplace factors to grow. But where there is poor PSC adverse psychosocial factors and poor employee health are more prevalent[xv]. Deliberately enacting these values with workplace practices is perhaps the most impactful activity an organization or leader can do within their scope of influence.

Strategy matters.

An inspirational speaker, one-off training, a shiny new app or email reminders about self-care are all examples of activities that may not be connected to an overall strategy. In keeping with the research into PSC, disconnected efforts are unlikely to change the overall culture and workplace health and employee engagement outcomes. Organizations are made of human beings, not human doers, and as such human beings respond to elements of the workplace, make judgements about what they experience, and experience positive or unpleasant emotional and physical responses which impact health and behavioural choices. So on one hand, work demands and pressure can be almost unbearable but the company is offering an mindfulness app. At best, the employee perceives this as an annoyance, at its worst, this breaks the psychological contract and the employee experiences injustice, believing the employer disingenuous in ignoring its harmful work conditions.

Using an overall strategy, crafted using the steps outlined in the Standards above combined with evidence referenced later, can direct which activities will be impactful. Deloitte found companies who had invested time in sustained execution of strategy had less employees off work on disability than others who had little sustained effort. The best impact was for organizations with the longest track record[xvi].

It matters which activities you do.

Each organization is unique in its workplace hazards and resources and must define what it needs and pick the tools to accomplish that outcome. Often organizations have quite a few great activities and need to acknowledge their success. But not all activities will create the desired impact and rarely is there a “silver bullet” and interventions should align with all components of the Integrated Model. For example, resilience training has been shown to have little impact on its own but specific problem solving skills training has greater impact[xvii]. Deloitte found benefits from prevention, good work accommodation programs, and extended health benefit access[xvi].

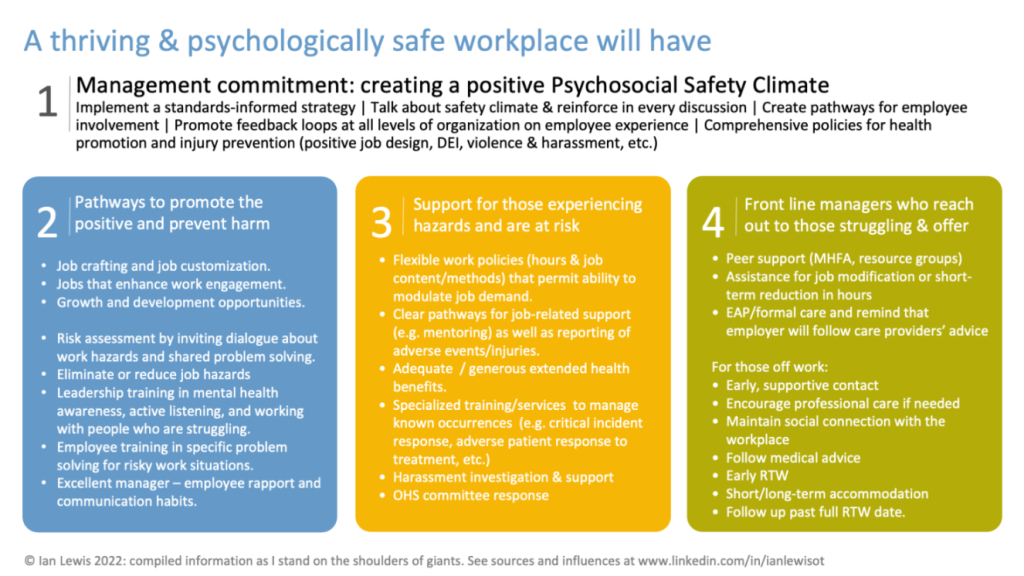

Putting evidence-informed workplace wellbeing activities on one page:

It is hard to sum up everything on one page. But here is my attempt to compile a lot of good evidence-informed approaches on one page:

What is your next step?

Everyone and all organizations are at various stages of change. You may be convinced but perhaps others on your team are not. Perhaps you’re all in agreement. Good starter questions for a team meeting, depending on your context, could be:

- What has gotten in the way of being engaged with our work this week?

- What’s one action you did this week that reinforced positive coping?

- What is our strategy to maintain employee health and productive capacity of our workforce?

- How will this next action (e.g. implementing a zero-hours contract) affect the wellbeing of our workforce?

But don’t wait for the whole organization to get on board. I love this quote attributed to Napoleon Hill: “Don’t wait. The time will never be just right. Start where you stand, and work whatever tools you may have at your command and better tools will be found as you go along.”

Be the leader or co-worker you’d like others to be to you.

Ian Lewis is a Registered Occupational Therapist who practices in Saskatchewan, Canada. His interest in workplace health comes from a career working with people injured at work or unable to work due to other physical or mental health problems and helping them return to health and helping their employer to support their return to work.

[i] Anthony D LaMontagne et al., “Workplace Mental Health: Developing an Integrated Intervention Approach,” BMC Psychiatry 14, no. 1 (December 2014): 131, https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-131.

[ii] Shu-Ping Chen, Wen-Pin Chang, and Heather Stuart, “Self-Reflection and Screening Mental Health on Canadian Campuses: Validation of the Mental Health Continuum Model,” BMC Psychology 8, no. 1 (July 29, 2020): 76, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-020-00446-w.

[iii] Statistics Canada, “Mental Health Indicators,” September 18, 2013, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310046501.

[iv] Joanne C Enticott et al., “Prevalence of Psychological Distress: How Do Australia and Canada Compare?,” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 52, no. 3 (March 2018): 227–38, https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417708612.

[v] Statistics Canada Government of Canada, “Trends in the Prevalence of Depression and Anxiety Disorders among Working-Age Canadian Adults between 2000 and 2016,” December 16, 2020, https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2020012/article/00002-eng.htm.

[vi] Stevan E. Hobfoll et al., “Conservation of Resources in the Organizational Context: The Reality of Resources and Their Consequences,” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5, no. 1 (January 21, 2018): 103–28, https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640.

[vii] Arnold B. Bakker and Evangelia Demerouti, “Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking Stock and Looking Forward.,” Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 22, no. 3 (July 2017): 273–85, https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056.

[viii] Tino Lesener, Burkhard Gusy, and Christine Wolter, “The Job Demands-Resources Model: A Meta-Analytic Review of Longitudinal Studies,” Work & Stress 33, no. 1 (January 2, 2019): 76–103, https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2018.1529065.

[ix] Arnold B. Bakker and Yiqing Wang, “Self-Undermining Behavior at Work: Evidence of Construct and Predictive Validity.,” International Journal of Stress Management 27, no. 3 (August 2020): 241–51, https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000150; Arnold B. Bakker and Juriena D. de Vries, “Job Demands–Resources Theory and Self-Regulation: New Explanations and Remedies for Job Burnout,” Anxiety, Stress, & Coping 34, no. 1 (January 2, 2021): 1–21, https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1797695.

[x] S. A. Ruhle et al., “‘To Work, or Not to Work, That Is the Question’ – Recent Trends and Avenues for Research on Presenteeism,” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 29, no. 3 (May 3, 2020): 344–63, https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1704734; Rodanthi Lemonaki et al., “Burnout and Job Performance: A Two-Wave Study on the Mediating Role of Employee Cognitive Functioning,” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 30, no. 5 (September 3, 2021): 692–704, https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2021.1892818.

[xi] International Organization for Standardization, “Occupational Health and Safety Management — Psychological Health and Safety at Work — Guidelines for Managing Psychosocial Risks” (International Standards Organization, 2021), https://www.iso.org/standard/64283.html.

[xii] Health and Safety Executive, “HSE Management Standards Indicator Tool,” 2017, https://www.hse.gov.uk/stress/assets/docs/indicatortool.pdf.

[xiii] Canadian Standards Association Group and Bureau de Normalisation du Quebec, “CAN/CSA-Z1003-13/BNQ 9700-803/2013 National Standard of Canada Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace — Prevention, Promotion, and Guidance to Staged Implementation” (CSA Group, 2013).

[xiv] Garry B. Hall, Maureen F. Dollard, and Jane Coward, “Psychosocial Safety Climate: Development of the PSC-12.,” International Journal of Stress Management 17, no. 4 (2010): 353–83, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021320.

[xv] Maureen F Dollard et al., “Psychosocial Safety Climate (PSC) and Enacted PSC for Workplace Bullying and Psychological Health Problem Reduction,” European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology 26, no. 6 (November 2, 2017): 844–57, https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2017.1380626; May Young Loh et al., “Psychosocial Safety Climate as a Moderator of the Moderators: Contextualizing JDR Models and Emotional Demands Effects,” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 91, no. 3 (September 2018): 620–44, https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12211; Maureen F. Dollard, “Psychosocial Safety Climate: A Lead Indicator of Workplace Psychological Health and Engagement and a Precursor to Intervention Success.,” in Improving Organizational Interventions for Stress and Well-Being, ed. Caroline Biron, Maria Karanika-Murray, and Cary Cooper (East Suffex: Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2012), 77–101.

[xvi] Deloitte Canada, “The ROI in Workplace Mental Health Programs: Good for People, Good for Business,” 2019, https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ca/Documents/about-deloitte/ca-en-about-blueprint-for-workplace-mental-health-final-aoda.pdf.

[xvii] Marc White, “Focus on Tomorrow: Identification, Control and Prevention of Work-Related Psychosocial Hazards and Social Conditions Contributing to Mental Health Disorders and Prolonged Work Absence” (Work Wellness and Disability Prevention Institute, April 20, 2020), https://workwellnessinstitute.org/research/978-1-988875-02-6.